In Parma, Italy, 31 years ago, a monkey sat alone in a laboratory. Specifically, a macaque, with thin wires implanted in a premotor cortex region of its brain called F5—the part that is stimulated when the monkey does or plans things. A graduate student, returning to the lab from lunch, carried an ice cream cone and started to eat it in front of the monkey with an ice cream cone in one hand. The monitor sounded with the firing of neurons, even though the monkey was simply observing the student about to eat the cone.

The researchers who were studying the monkey were led by Giacomo Rizzolatti, a neuroscientist at the University of Parma, who had noticed an earlier phenomenon with peanuts. The same brain cells fired when the monkey watched humans or other primates bring peanuts to their mouths as when the monkey itself brought the peanut to its mouth. The same thing happened with other fruits like bananas and raisins.

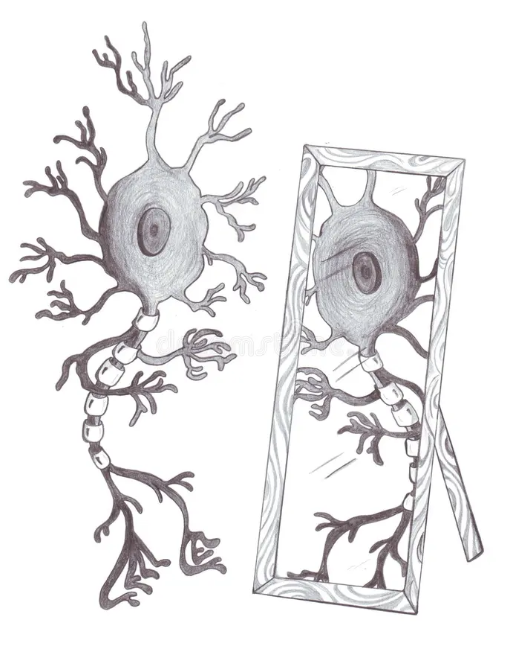

In a recent interview, Dr. Rizzolatti said that it took “us several years to believe what we were seeing.” What they were seeing was a special class of cells, now known as mirror neurons, that fire when you see someone do something and when you do that thing on your own. This accidental discovery would turn out to be revolutionary in our understanding of human empathy and connection. While monkeys have these special neurons, humans have developed far more sophisticated mirror neuron systems that don’t just copy actions — they help us understand intentions and emotions, which are at the very heart of social interaction.

This biological mechanism explains why we wince when we see someone step on Legos or stub their toe, or why our hearts flutter when we watch someone in a horror movie. Our mirror neurons are quite literally simulating these experiences in our own minds, creating a connection between our perceptions of self and other that forms the basis of empathy.

Mirror neurons help explain why a mother instinctively opens her mouth while feeding her baby, why we catch ourselves mimicking the accents of people we are talking to, and why watching someone else’s embarrassment can make us blush. They explain the chameleon effect (when you stick out your tongue to a baby, they do the same) and the Michelangelo effect (when couples are married to each other for a long time, they begin to mimic each other’s expressions). They’re the neural basis for that gut-level understanding we call empathy: the ability to truly feel what others feel.

We are wired to connect, understand, and feel what others feel. This is why we are fundamentally social creatures. According to Dr. Keysers, a French and German neuroscientist at the University of Parma, people who rank high on an empathy scale have particularly active neuron systems. Some researchers believe that autism may involve impaired mirror neurons. A study published in Nature Neuroscience by Dr. Mirella Dapretto at UCLA found that while many people with autism can identify emotional expressions and imitate them, they don’t feel the emotional significance of the imitated emotion; they may recognize sadness in another person’s face, but they don’t feel sad themselves.

As we face increasingly complex social challenges in our world, understanding these fundamental mechanisms of human connection becomes more important now than ever. Dr. Rizzolatti’s accidental discovery opens up new possibilities for creating empathy and understanding. Empathy is built into our biology; we can work with these natural mechanisms rather than against them. In a time known for declining empathy, this understanding offers hope: our brains are naturally wired for connection. We just need to create the conditions that allow these ancient neural networks to do their work.

Works Cited:

Amelie84. Mirror Neuron Illustrations & Vectors, www.dreamstime.com/royalty-free-stock-images-mirror-neuron-image25595789. Accessed 2 Nov. 2024.

Blakeslee, Sandra. “Cells That Read Minds.” The New York Times, 10 Jan. 2006, www.nytimes.com/2006/01/10/science/cells-that-read-minds.html.

“I Feel Your Pain, but Why?” Psychology Today, 2024, www.psychologytoday.com/ie/blog/ethical-wisdom/201103/i-feel-your-pain-but-why. Accessed 2 Nov. 2024.

Winerman, Lea. “The Mind’s Mirror.” American Psychological Association, Oct. 2005, www.apa.org/monitor/oct05/mirror.

Sleep Deprievation vs. UCVTS

Sleep Deprievation vs. UCVTS